For Black History Month 2020, Wakefield Museums & Castles are exploring four stories related to British slave ownership in the early 1800s. This week, we are focusing on our collections and how we can reveal hidden stories from objects that at first glance seem to be unrelated.

It can be surprising how many different and diverse stories museum objects can tell.

The Triangle of Trade

|

| Banknote of the Wakefield Bank, Ingram, Kennett and Ingram, 1800 |

Captain Francis Ingram of Wakefield used the profits from trading in enslaved people to start Wakefield’s first bank. In the 1770s and 1780s he was a major figure in the slave trade, involved in 105 voyages, which took away close to 34,000 slaves from Africa. It is estimated that these ships delivered just over 29,000 people to the Americas, meaning that around 5,000 died making the journey across the Atlantic Ocean.

Ingram’s business was part of the so called Triangle of Trade. British merchants like Ingram sailed from ports such as Liverpool and traded goods for enslaved Black people from African merchants in ports along the West African coast.

The enslaved people were tightly packed into ships, which then travelled across the Atlantic to the British colonies in North and South America and the Caribbean. Many enslaved men, women and children died in the crossing. The ships were unsanitary and overcrowded.

The industrial revolution in Britain in the 1700s and 1800s relied on the exploitation of enslaved people in the British colonies. The merchants traded the enslaved to plantation owners in return for the goods they would be put to work to grow and harvest. The key products were cotton, coffee, rum, sugar, and tobacco. These goods were then shipped back to Europe and made their way to wardrobes, kitchens, dining tables and pockets in Britain. Some would then complete the cycle and be shipped to Africa to be traded for more enslaved workers.

The products of slavery

The use of slave labour enabled mass production, meaning that expensive commodities became more affordable to less wealthy families and began to appear in homes across the country. The household objects associated with these luxury goods eventually arrived in our museum collections.

|

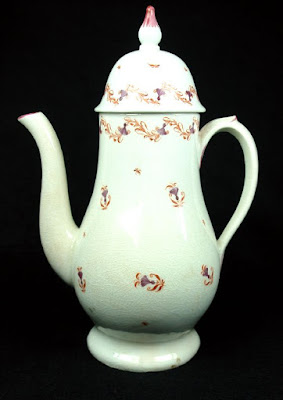

Coffee pot, Newhall, 1820s |

|

Sugar nippers, early 1800s Sugar arrived at a household in a cone or

‘loaf’. It was broken up with a sugar axe or hammer and then nippers like these

were used to cut off smaller chunks. |

|

| Sugar bowl, D. Dunderdale and Co., Castleford, 1790 – 1821 |

|

Tobacco box, late 1700s |

Shamefully, the lives of most enslaved people from the early 1800s are absent from history. But their stories and suffering are often hidden in plain sight in our collections and displays, and the social and industrial history of the nation.

This is the third article in our Black History Month series looking at Wakefield’s links to slavery. The final post next week will consider how the Waterton family were entangled with the practice of slavery in the late 1700s and early 1800s and what Wakefield Museum is doing to address it.

No comments:

Post a Comment

We would love your comments - though they may take a day or two to appear.