Bathing was an important part of Roman life. Rome itself had nearly a thousand bath houses in the 4th century AD, the largest of which had room for 3,000 bathers. The Romans took this enthusiasm for bathing all across their Empire, including to Castleford.

Revealing the bath house

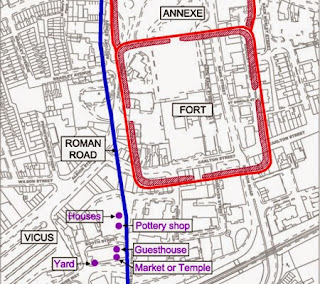

Castleford’s bath house was discovered in 1978 by Ron Jeffries, an enthusiastic local amateur archaeologist. It is next to (and partly underneath) the Savile Road / Church Street roundabout, so it couldn’t be completely excavated, but enough was found to be sure of its layout.

|

| Amateur archaeologist, Ron Jeffries, at a dig in Castleford |

|

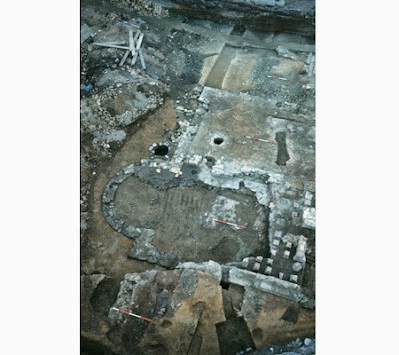

| Digs revealed the almost complete ground plan of the Castleford bath house |

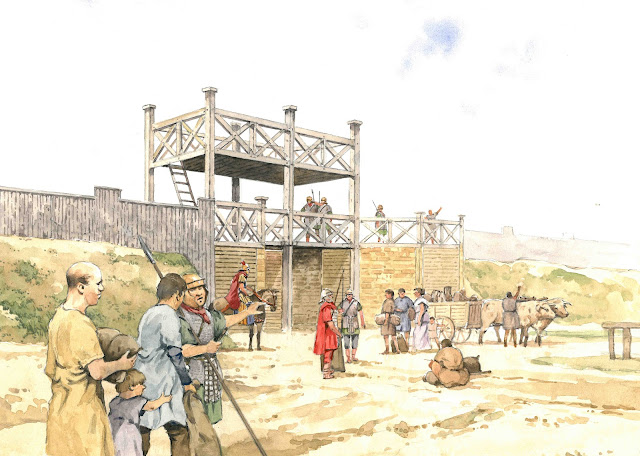

It was in an annexe to the main fort and was originally built by and for the army. The whole building was built of brick and stone and probably decorated with statues. It would have been one of the more impressive buildings in town.

Clever engineering

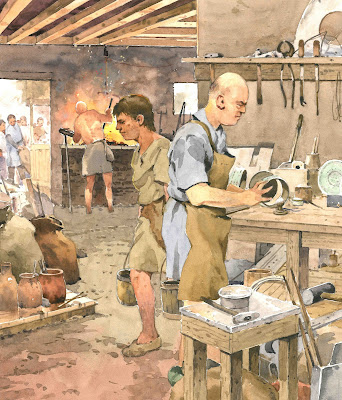

Roman soldiers usually built their own barracks and forts but the bath house was a specialist project, probably built by professional engineers, not the local troops. We think this because the tiles in it are stamped with the mark of the 9th Legion Hispania, the main legionary unit based in York, rather than the 4th Cohort of Gauls, the unit based at Castleford.

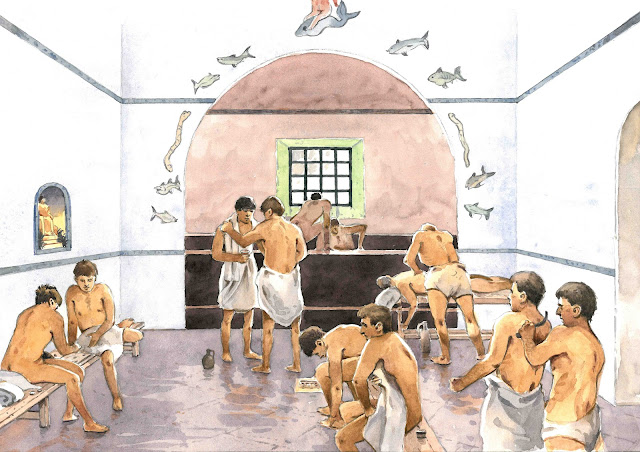

The building itself was about 25 metres long and followed a standard design. Roman baths were more like Turkish baths than modern swimming pools, based on relaxation and perspiration. The first room you entered was the changing room. There were then three rooms that got hotter as you went on. The last of these probably had a hot bath in it. Finally there was a much larger cold water plunge pool after you left the hot room, made of a special concrete that looked like marble.

|

The rooms were heated by large furnaces, which piped hot air through a clever series of ducts under the floors and in the walls. Fresh water probably came from a spring, and the dirty water could be piped away to the nearby River Aire. A stone tablet dedicated to water nymphs suggests that the local spring was special, maybe having magical healing powers, making the baths even better.

Bathing and beauty

To get clean in a Roman bath you would have rubbed oil into your skin. Then as you got hotter and hotter, and started sweating, the dirt and sweat would have mixed with the oil. This mix of oil, dirt and sweat would then be scraped off with a special curved blunt blade. At the same time you could have other cosmetic and beauty treatments. These tweezers for plucking hairs were found in the bath house.

Fun and games

Roman bathing was about far more than just getting clean. It was also for relaxation and especially for socialising. There would have been drinks and snacks available while you chatted with friends, or networked and did some business with associates. A gaming counter found in the bath house shows you would also have played games and gambled.

|

| Roman gaming counters and die, made from bone |

You can have a go at bathing like a Roman at home! Join archaeologist, Sally Pointer, to find out how to make your own rose scented bathing oil, inspired by the Lagentium bath house.

Can you recreate the scene from inside the bath house? How long will it to take you to complete our Rome From Home jigsaw?